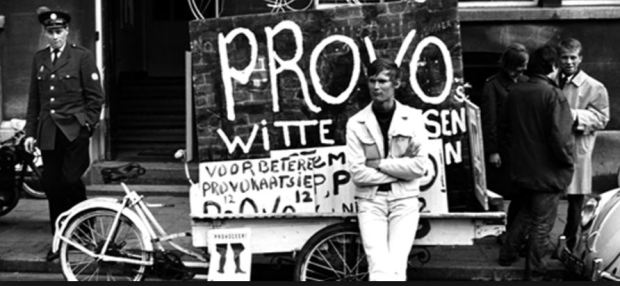

To understand Luud Schimmelpennink’s White Bicycle Plan, it helps to have a look at the broader context of values, philosophy and politics that were prevailing in Amsterdam at that time – the Provos, a Dutch counterculture youth movement in the mid-1960s.

And if one concludes that this was more or less what was going on in other parts of Europe and North America, you would be right. And a bit wrong. The Dutch were digging deeper. At least this part of Dutch society was.

The Provos were indeed worried about the environment, aware that the huge increase in the number of cars were challenging and transforming their cities and desired ways of life, deeply troubled by the war in Vietnam and colonialism, continuing lack of sensitivity to issues important for women, lack of adequate housing for all but the most wealthy, and more generally issues of equity and fairness.

And all this against the unquestioning stodginess and general lack of creativity of mainline politicians and voters, they decided to ask other hard questions about other things. The Provos sought to provoke the public and the institutions and behaviour in non-violent ways, aiming to shatter the self-righteousness of the authorities. And to challenge the establishment through provoking. And irritating. But also, to propose some alternative visions of society.

The White Plans

Among these alternative visions of society were the White Plans, of which the most famous was Schimmelpenninck’s White Bicycle Plan. But there were others. And to fully understand the White Bicycles, we really need to have at least a quick look at these others, starting with the bikes. (Following with thanks to sections of Wikipedia entry on The White Plans- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Provo_(movement))

The political wing of the Provos won a seat on the city council of Amsterdam, and developed the “White Plans”. The most famous of those is the “White Bicycle Plan”, which aimed to improve Amsterdam’s transport problem. Generally, the plans sought to address social problems and make Amsterdam more liveable.

White Bicycle Plan

The most famous of these was the White Bicycle Plan: Initiated by Luud Schimmelpennink, the White Bicycle Plan proposed the closing of central Amsterdam to all motorised traffic, including motorbikes, with the intent to improve public transport frequency by more than 40% and to save two million guilders per year. Taxis were accepted as semi-public transport, but would have to be electrically powered and have a maximum speed of 25 m.p.h.

The Provos that: the municipality would buy 20,000 white bikes per year, which were to be public property and free for everybody to use. After the plans were rejected by the city authorities, the Provos decided to go ahead anyway. They painted 50 bikes white and left them on streets for public use. The police impounded the bikes, as they violated municipal law forbidding citizens to leave bikes without locking them. After the bikes had been returned to the Provos, they equipped them all with combination locks and painted the combinations on the bicycles.

Other White Plans

Other White Plans likewise attacked important matters of society, which the young Provos felt were met with widespread public indifference. These included:

- White Chimney Plan: Proposed that air polluters be taxed and the chimneys of serious polluters painted white.

- White Women Plan: Proposed a network of clinics offering advice and contraceptives, mainly for the benefit of women and girls, and with the intention to reduce unwanted pregnancies. The plan was for girls of sixteen to be invited to visit the clinic, and advocated for schools to teach sex education. The White Women Plan also argued that it is irresponsible to enter marriage as a virgin.

- White Chicken Plan: Proposal for the reorganization of the Amsterdam police (called “kip” in Dutch slang, meaning “chicken”). Under the plan, the police would be disarmed and placed under the jurisdiction of the municipal council rather than the burgemeester (mayor). Municipalities would then be able to democratically elect their own chief of police. The Provos intended for this revised structure to transform the police from guard to social worker

- White Housing Plan: The plan sought to address Amsterdam’s acute housing problem by banning speculation in house building, and by promoting the squatting of empty buildings. The plan envisioned Waterlooplein as an open-air market and advocated abandoning plans for a new town hall.

- White Kids Plan: The plan proposed shared parenting in groups of five couples. Parents would take turns to care for the group’s children on a different day of the week.

- White Victim Plan: The Plan proposed that anyone having caused death while driving would have to build a warning memorial on the site of the traffic collision by carving the victim’s outline one inch deep into the pavement and filling it with white mortar.

- White Car Plan (Witkar) A car-sharing project proposed by Schimmelpennink featuring electric cars which could be used by the people. It was later realised in a limited fashion as the Witkar system from 1974 until 1986.

(More on this important extension of the original White Bicycle Plan to follow here.to follow.)

So now, armed with this bit of important context we can start to dig deeper into what was making Luud tick.

# # #

More on grassroots support for Luud’s outstanding contributions

References:

* World Streets: The Politics of Transport in Cities https://goo.gl/42JSQ6

* Facebook: https://goo.gl/Wvc5BG

* Twitter: https://twitter.com/ThanksLudd

* LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/8598247

* Direct mail for campaign: ThanksLuud@ecoplan.org

* Contact organizer: E. eric.britton@ecoplan.org. S. newmobbility T. +336 5088 0787.

# # #

About Luud Schimmelpennink:

A great idea has wings:

Dutch social inventor, industrial designer, entrepreneur and politician, since the mid  1960s Luud Schimmelpennink has been active in creating new low-carbon products and projects, with special focus on sustainable transportation concepts. His work aims to both reducing the number of conventional motor cars in urban areas for environmental and public health reasons, and provide people with viable alternative means of getting around in the city. Luud is the person who set the pattern for free (shared) city bike projects in Amsterdam back in the sixties. And if most of his original White Bicycles eventually disappeared, his example blazed the way to more work and thought, bringing us to where we are today (worldwide more than 2.5 million public bikes in 1138 cities on all continents. Proof that “a great idea has wings”.

1960s Luud Schimmelpennink has been active in creating new low-carbon products and projects, with special focus on sustainable transportation concepts. His work aims to both reducing the number of conventional motor cars in urban areas for environmental and public health reasons, and provide people with viable alternative means of getting around in the city. Luud is the person who set the pattern for free (shared) city bike projects in Amsterdam back in the sixties. And if most of his original White Bicycles eventually disappeared, his example blazed the way to more work and thought, bringing us to where we are today (worldwide more than 2.5 million public bikes in 1138 cities on all continents. Proof that “a great idea has wings”.

In 2006 he was elected again to the Amsterdam Municipal Council, and is currently working on a new WitKar-type project for Amsterdam as well as continuing to promote community cycles in Amsterdam and elsewhere. Luud is Managing Director of the Ytech Innovation Centre in Amsterdam

# # #

About the author:

Eric Britton

9, rue Gabillot, 69003 Lyon France

Bio: Trained as a development economist, Eric Britton is a public entrepreneur specializing in the field of sustainability and social justice. Professor of Sustainable Development, Economy and Democracy at the Institut Supérieur de Gestion (Paris), he is also MD of EcoPlan Association, an independent advisory network providing strategic counsel for government and business on policy and decision issues involving complex systems, social-technical change and sustainable development. Founding editor of World Streets, his latest work focuses on the subject of equity, economy and efficiency in city transport and public space, and helping governments to ask the right questions — and in the process, find practical solutions to urgent climate, mobility, life quality and job creation issues. More at: http://wp.me/PsKUY-2p7

: